A Way We Were

Hearing the news yesterday that Robert Redford had passed away reminded me of one of the most moving, and bittersweet, memories that Prince shared with us toward the end of his life. It began as an uncharacteristically direct moment of vulnerability, and eventually turned into a conversation about the one most important lesson he wanted everyone to learn about his life’s work. It’s one that seems more relevant than ever today.

Prince’s final tour was called “Piano & a Microphone”, an intimate show where he’d play his own songs, and songs that had meant a lot to him growing up, while telling stories of his life or of the moments that inspired those songs.

In those last shows, including at the final concert of his life, Prince would play a searing, heartfelt medley of Bob Marley’s “Waiting in Vain” and his own “If I Was Your Girlfriend”.

During the song, Prince paused and put up a still photo of Robert Redford and Barbara Streisand from “The Way We Were”, asking the audience if they remembered the scene in the film where the couple breaks up, only for Streisand’s character to immediately call Redford’s character to console her despite being her ex.

Prince then resumes his song with the next verse, “would u run 2 me if somebody hurt u, even if that somebody was me?” It’s a surprisingly revealing look at the inspiration, or at least an artistic connection, behind one of Prince’s most beloved songs. Though it’s far from one of his biggest hits or his best-known compositions, “If I Was Your Girlfriend” is beloved by fans for its groundbreaking bending of gender, its genuinely unique production, and especially the empathy and vulnerability of its narrative. And now we saw Prince dropping his long-maintained stage persona to talk about a romantic movie that came out when he was 15 years old. We can only imagine the impression it left on him as a teenager, enough for him to reference it more than 40 years later with absolutely no loss in emotional resonance.

Prince’s Version

In an era when an entire generation has grown up listening to “Taylor’s Version” of a recording, fans’ fluency about intellectual property and artists’ rights of ownership is very high. But in the 80s and 90s, it was often considered gauche for an artist to talk about such commercial concerns, and very few mainstream media outlets even mentioned the long history of Black artists having had their work exploited and extracted by the music industry over the years.

After becoming one of the most popular and consequential artists of the 1980s, Prince started, in the early 1990s, to focus his career on getting control of his artistic output — specifically his master recordings. During this time, he said that the one thing he wanted to be remembered for was “If u don’t own your masters, then your masters own u.”

That message of artistic control over creativity has always stuck with me, and I was reminded of it again when Prince had performed his beautiful, moving cover of that Marley song mashed up with one of his own greatest compositions.

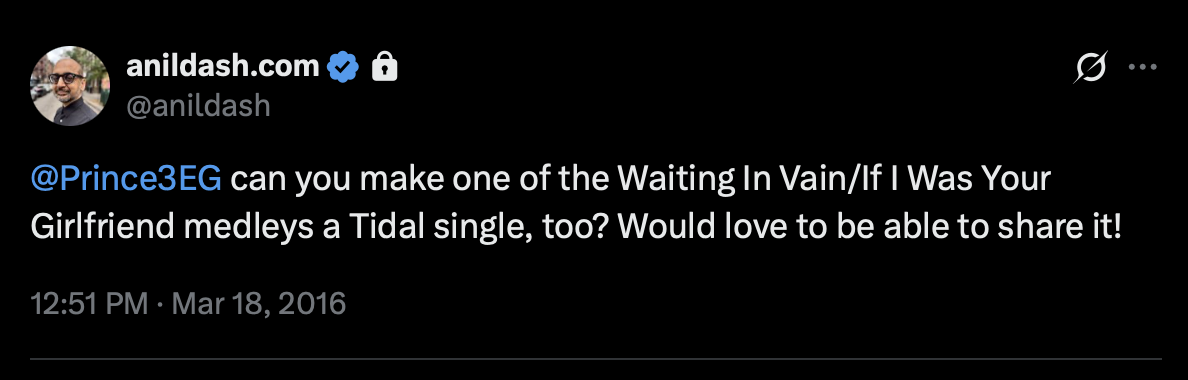

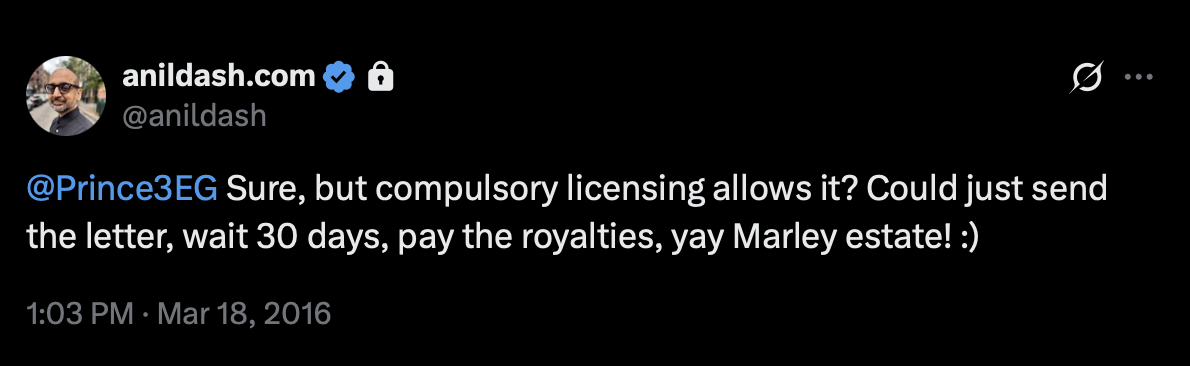

So I asked him if he would release a recording of his live performance of the track for us fans to be able to listen to legally.

He responded in a deleted tweet (he usually deleted nearly all of his tweets shortly after posting) that he would have to ask the Marley estate's permission in order to release the recording. I pointed out that he technically didn't need to do so, since the legal regime of compulsory licensing meant that artists could record a cover without having to ask the original composer. This was, for example, how Sinead O'Connor had been able to record his composition "Nothing Compares 2 U" without having had to ask for his clearance.

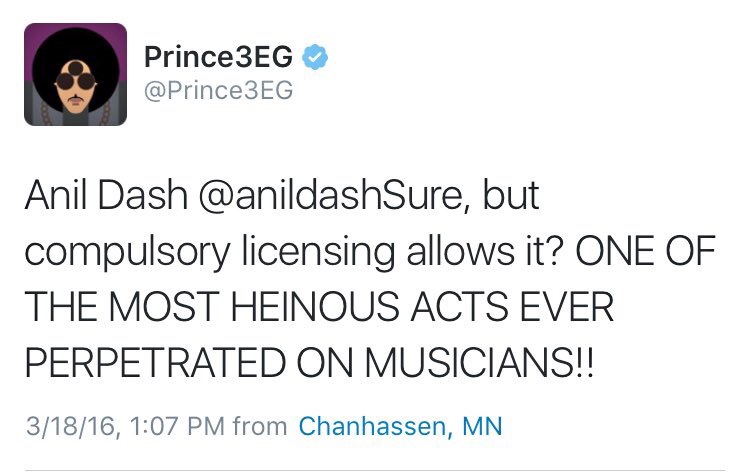

Prince's response was, well... classic Prince. (He tended to respond to tweets by copying-and-pasting them into his responses instead of quoting them.)

ONE OF THE MOST HEINOUS ACTS EVER PERPETRATED ON MUSICIANS!! seems to be fairly consistent with his views about how artists should have been able to maintain full control over their work. Well, at least how he should have been able to maintain full control over his work — Prince played covers of other artists without their prior consent all the time. In fact, the true genius of how Prince played the greatest Super Bowl halftime show of all time was due to his deep and brilliantly subtle use of cover songs as incredibly thoughtful cultural commentary.

But that complexity aside, what I largely took away from reflecting on this exchange from almost a decade ago was how much I miss having this kind of interplay about artists' rights and artistic influence with smart, engaged, thoughtful creators.

Redford fought throughout his career for underrepresented creators to have the stage (and the screen) at platforms like Sundance, just as so many institutions falter and back off of support for those vital creators. He gave voice to narratives like the immorality of McCarthyism in films like The Way We Were, just as a new wave of equally virulent witch hunts begins to ramp up. His most legendary roles like All The President's Men ring most resonant when we see The Washington Post making a mockery of itself against the backdrop of a presidency whose corruption is even more depraved, carried out by those who don't even bother to hide it.

Similarly, Prince shared his stages and studios with an incredibly broad and diverse set of collaborators, and constantly reminded them that they needed to walk away with real ownership of their work. He fought the biggest and most powerful companies that attempted to control every aspect of culture and media, and even when it took decades to do so, wrested control of his work back into his own hands, all while pioneering so many of the tools and technologies and techniques that would inspire a new generation of artists to demand the rights they deserve. Just as importantly, he never backed down from using the art he created to speak up on issues of social justice and equity, standing on the biggest stages to plainly speak to the humanity and dignity of every person.

Waiting

But beyond those big headlines, there are the simple acts that these artists performed on a daily basis. They made art where they allowed themselves to be vulnerable. They dressed with style all the time, even when nobody was looking. They let themselves be inspired by the unexpected, by other forms of art, by everything around them. And they made a space for the next generation to follow in their footsteps, to create on their own terms, to go even further after they're gone.