It feels like 2004 again.

I keep having a conversation with people around the tech world about how the industry’s current state of change — especially the potential disruption of incumbents — feels like nothing so much as a cyclical repeat of what we saw in 2004.

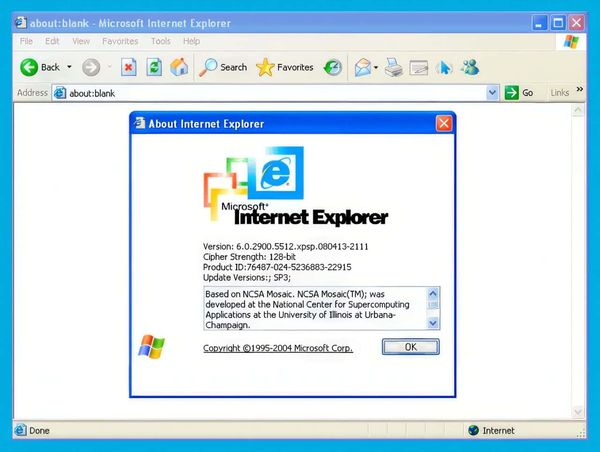

A generation ago, those of us in tech might talk to our friends or family and hear them say, "I think the ads in my Hotmail account are terrible, and I can’t send any attachments. And Yahoo search is getting worse, plus Mapquest is so slow. Plus, I need to get all my friends off of AOL, and I don’t even know what anyone is doing on Friendster anymore. And I can’t deal with all the popup ads on Internet Explorer.."

Today, though, it’s Google search that’s rapidly getting worse, and Twitter that your friends are trying to quit. Cory Doctorow hadn’t coined "enshittification" yet in 2004, but he was certainly there warning us about it, and, well… some things never change.

Iterestingly, most of the people who’ve heard me say this over the last year or so think that I’m complaining or lamenting the situation, but I’m actually excited about it. That malaise by the big players in tech a generation ago yielded an exciting and inspiring new wave of innovations. While much of the money in big tech was chasing distractions back in 2004, many communities of small, independent creators on the open web were making the new pillars of web culture — many of which are still standing to this day.

When I wrote The Web We Lost, it was largely this flourishing of independent creativity and open collaboration that was I was largely lamenting. But I was wrong to think it was lost. It was merely dormant, beaten into near-irrelevance by the domination of the giant tech players. At the start of this year, I wrote The Internet Is About To Get Weird Again, which began by calling back to the Internet of 2000. In thinking more about it, though, we more closely resemble the Internet of a few years later, where the crash of the dot-com bubble and the stock market had the same effect that the popping of the crypto bubble did: the casuals who were just trying to make a quick buck are much less likely to jump in the pool. There’s far more space for weirdness and passion and actually making new shit.

Twenty years ago, we saw the first large-scale social networks — and there were lots of them, not just one. We saw a passionate community rise up and challenge the most powerful tech monopoly that had ever existed, and create a viable mainstream consumer option for the fundamental tool everyone uses to access the internet. The platforms for publishing and sharing online were democratized, and the radical, open architecture of formats like podcasts were codified.

So it’s no surprise to me that the renaissance of the open, human internet is in full swing. And this time, we have the advantage of knowing how the bad guys might try to take advantage of it, so we might not be doomed to repeat the most painful parts of the cycle that followed.