The World is Getting Better. Quickly.

Last week, I had a chance to sit down with Bill Gates as part of a small group, in a discussion focused around the release of his annual letter and the progress that has been made against the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals. (You can also read his annual letter as a 6.3MB PDF.) I’ll write separately about what it was like having a conversation with Bill Gates, but the biggest highlight that came from the meeting was a simple lesson:

The world is getting better, faster, than we could ever have imagined.

For those of us who are fortunate enough to live in wealthy communities or countries, we have a common set of reference points we use to describe the world’s most intractable, upsetting, unimaginable injustices. Often, we only mention these horrible realities in minimizing our own woes: “Well, that’s annoying, but it’s hardly as bad as children starving in Africa.” Or “Yeah, this is important, but it’s not like it’s the cure for AIDS.” Or the omnipresent description of any issue as a “First World Problem”.

But let’s, for once, look at the actual data around developing world problems. Not our condescending, world-away displays of emotion, or our slacktivist tendencies to see a retweet as meaningful action, but the actual numbers and metrics about how progress is happening for the world’s poorest people. Though metrics and measurements are always fraught and flawed, Gates’ single biggest emphasis was the idea that measurable progress and metrics are necessary for any meaningful improvements to happen in the lives of the world’s poor. So how are we doing?

The World Has Changed

The results are astounding. Even if we caveat that every measurement is imprecise, that billionaire philanthropists are going to favor data that strengthens their points, and that some of the most significant problems are difficult to attach metrics to, it’s inarguable that the past two decades have seen the greatest leap forward in the lives of the global poor in the history of humanity. Some highlights:

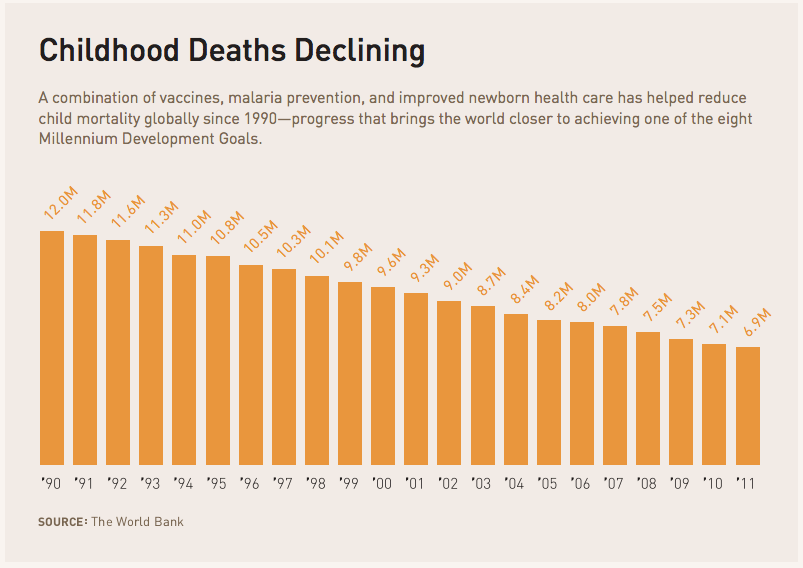

- Children are 1/3 less likely to die before age five than they were in 1990. The global childhood mortality rate for kids under 5 has dropped from 88 in 1000 in 1990 to 57 in 1000 in 2010. The global infant mortality rate for kids dying before age one has plunged from 61 in 1000 to 40 in 1000. Now, any child dying is of course one child too many, but this is astounding progress to have made in just twenty years.

- In the past 30 years, the percentage of children who receive key immunizations such as the DTP vaccine has quadrupled.

-

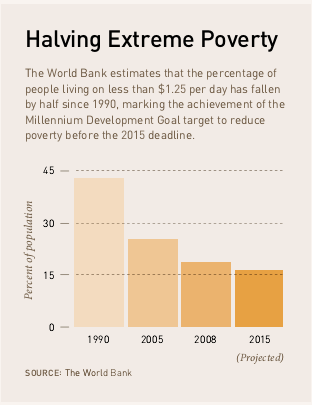

The percentage of people in the world living on less than $1.25 per day has been cut in half since 1990, ahead of the schedule of the Millennium Development Goals which hoped to reach this target by 2015.

-

The number of deaths to tuberculosis has been cut 40% in the past twenty years.

-

The consumption of ozone-depleting substances has been cut 85% globally in the last thirty years.

-

The percentage of urban dwellers living in slums globally has been cut from 46.2% to 32.7% in the last twenty years.

And there’s more progress in hunger and contraception, in sustainability and education, against AIDS and illiteracy. After reading the Gates annual letter and following up by reviewing the UN’s ugly-but-data-rich Millennium Development Goals statistics site, I was surprised by how much progress has been made in the years since I’ve been an adult, and just how little I’ve heard about the big picture despite the fact that I’d like to keep informed about such things.

I’m not a pollyanna — there’s a lot of work to be done. But I can personally attest to the profound effect that basic improvements like clean drinking water can have in people’s lives.

Today, we often use the world’s biggest problems as metaphors for impossibility. But the evidence shows that, actually, we’re really good at solving even the most intimidating challenges in the world. What we’re lacking is the ability to communicate effectively about how we make progress, so that we can galvanize even more investment of resources, time and effort to tackling the problems we have left.

Other Perspectives

Fortunately, everyone else who participated in the roundtable discussion has also posted their thoughts; I recommend reading them all.

- Jason Kottke summarizes the letter and reaches a similar conclusion to mine: “If you read the whole thing, you’ll likely be surprised, as I was, at how much has been accomplished over the past 10-15 years.” You should also see Jason’s account of Gates’ answers to his questions.

- Tyler Cowen’s excellent writeup addresses both the content and the tone of Gates’ responses, and shows how the measurement-based focus can change the perspective we have on these problems.

- I really appreciated Dana Goldstein’s take, which focused on Gates’ efforts around education, the foundation’s sole program which operates here in the United States. She also had a more personal take on the overall conversation.

- Finally, Luisa Kroll at Forbes offers her take on the conversation, focusing on Gates’ useful reframing of the way we evaluate colleges in the United States.