Google's Microsoft Moment

I’m not sure Google’s new Chrome OS announcement is that big a deal, or that the eventual product that gets released will actually have that much impact, but it’s a useful milestone in marking Google’s evolution towards becoming an older company with a distinctly different culture than they used to have.

This is, for lack of a better term, Google’s “Microsoft Moment”. This is the point when the difference between their internal conception of the company starts to diverge just a bit too far from the public perception of the company, and even starts to diverge from reality. At this inflection point, the reasons for doing new things at Google start to change.

Let me be clear: I don’t think Google is “turning evil”. Hell, I’ve caught a lot of flack for the fact that basically I don’t think Microsoftwas evil. But there are some notable trends going on across Google today that could cause the company to compromise its stated values and that will certainly cause people tothink Google is being evil, if not corrected. I’ll try to outline a few key cultural indicators from around Google.

Designing for corporate synergy, not for users

Google’s recent development work on applications for mobile devices has often been delivered exclusively as applications for their own Android platform instead of as iPhone applications, despite the fact that iPhones are roughly forty times more popular in the marketplace. iPhones are also much more popular outside of the United States than Android, further limiting the actual audience served by these applications. Now, it’s obviously good company policy to make sure to support Google’s own platforms, and Google does an admirable job of using generic open web technologies where possible to avoid having to choose between platforms at all. But choosing to leave the majority of users in a given market unaddressed because they are on a platform that is not part of your corporate goals is short-sighted and leaves a lingering sense of mistrust.

If you look at Microsoft ten years ago, or even as recently as five years ago, they had a tendency to say “Well, we’ve got a version that works on Windows Mobile.” or “This works on Internet Explorer” and feel that they’d done their job for addressing mobile or the web. Or Windows Media Player would connect to XBox but not to any other systems for sharing media. They were putting their corporate agenda ahead of what the marketplace had chosen as its preferred platforms. But after all these years, Microsoft’s internal teams have finally started to develop their web or mobile versions of products to work on competitor’s browsers and competitor’s mobile platforms, recognizing that they have to go where the users are, instead of favoring only the platforms created by their corporate siblings. Google appears to be headed the other way.

Forgetting what the real world uses, and favoring what’s convenient for your own business goals is a quick way to have customers think you don’t care, and to indicate to partners or developers that pleasing Google is more important than pleasing customers.

Multiple competing product lines: Chrome OS and Android

This is one of the simplest and most obvious examples, after this week’s announcements: Google is now offering not one, but two mobile operating systems. While they undoubtedly share code, I can’t help but think back to ten years ago, when Microsoft was vehemently protesting about how much code was shared between the Windows NT/Windows 2000 operating systems and the Windows 95/98/ME operating systems. If I make a screen two inches smaller, should I use Android instead of Chrome OS? If the keyboard works with my fingers instead of my thumbs, I should use Chrome OS and not Android? I know Google is convinced its employees are smarter than everyone else in the world, but this is a product management problem, not a computer science problem.

Changing methods of communication

Within Google, I’m sure the perception is that their public-facing communications are still very “Googley”. Now, Google does an excellent job of maintaining and using an enormous number of official corporate blogs in dozens of languages for a rapidly-blossoming number of products and initiatives. But despite my admiration for that effort, and their commendable willingness to forgo the usual boring press releases, the way that the company communicates with the public has fundamentally changed, and not necessarily in a more human direction.

In lieu of blog posts or simple word-of-mouth, as helped popularize the Google search engine itself ten years ago, efforts like Chrome are being accompanied by television ads, complete with all of the production values of primetime TV. Instead of launching a new developer initiative by promoting an SDK on their blog, Google is filling convention centers, Apple-style, with day-long developer presentations and an Oprahesque giveaway of free phones under every seat. Instead of white papers, there are highly-produced comic books being distributed to the press to explain the value of Chrome.

Now, I actually support these types of outreach. Getting outside of the insular tech bubble requires higher production values and clearer messaging. But when Google evokes Apple or Microsoft or Oracle in its style of communicating ideas, and when cell phone ads on TV say “Powered by Google”, an average consumer’s conception of Google essentially shifts to seeing this company not as “those guys who do the search engine” but instead as another consumer electronics company, like Samsung or Sony, but a little more hip.

This would be okay, except that I doubt Google’s internal self-image as an organization has changed to reflect this new reality. “We’re not like some giant company with flashy TV ads — we’re just a bunch of geeks in Mountain View!” And while that might be true for the vast number of engineers who define the company’s internal culture, the external impression of Google being just another tech titan like Microsoft will gain footing, making the audience for Google’s messages less tolerant of ambiguity and less forgiving of mistakes.

Only the last generation of companies can be evil, not us!

Though it’s almost impossible to picture now, in the era when Microsoft was formed, IBM was synonymous with an almost Orwellian dominance of information technology. It’s been a full 40 years since the antitrust actions against IBM, and IBM is seen as a bastion of open-sourceness now, but Microsoft’s founding mindset clearly was shaped with the idea that “those old guys from the last generation are evil, and we’re the nimble, smart upstarts who are going to humanize this industry”. Sound familiar?

Though it’s hard to believe, the FTC’s first investigations against Microsoft began eighteen years ago. When Microsoft reached its apex in terms of public perception and industry respect, with the launch of Windows 95, the culture inside the company still largely saw themselves as upstarts against old, proprietary behemoths. Though Microsoft’s headcount has increased fivefold since then, at the time of Windows 95’s launch, they had about 17,000 employees.

Google’s headcount just passed roughly 20,000 employees. And most of those staff members are firmly convinced that evil, or at least incompetence, is a trait of the last generation’s dominant tech player: Microsoft. The idea that developers or customers might start to bristle at their dominance is met with the (true, yet irrelevant) argument about how open their data and platforms are. Eric Schmidt said yesterday that Chrome OS is so open that Microsoft could make Internet Explorer for it, though of course the effort of porting the browser would be prohibitively complex. By neatly inverting the framing of the conversation (“We didn’t bundle a browser with our OS, we bundled an OS with our browser!”), Google’s avoided having to confront the parallels between this moment in their corporate culture and Microsoft’s similar moment of ascendancy 15 years ago.

Still haven’t developed Theory of Mind

And finally, as I outlined two years ago, Google still hasn’t developed theory of mind. From my piece then:

This shortcoming exists at a deep cultural level within the organization, and it keeps manifesting itself in the decisions that the company makes about its products and services. The flaw is one that is perpetuated by insularity, and will only be remedied by becoming more open to outside ideas and more aware of how people outside the company think, work and live.

Worse, because most of the dedicated detractors of Google have been either competing companies or nutjobs, it’s been hard for Googlers to take criticisms seriously. That makes it easy to have defensiveness or dismissal of criticisms become a default response.

Conclusion

Google has made commendable steps towards communicating with those outside of its sphere of influence in the tech world. But the messages will be incomplete or insufficient as long as Google doesn’t truly internalize and accept that its public perception is about to change radically. The era of Google as a trusted, “non-evil” startup whose actions are automatically assumed to be benevolent is over.

Years ago, GMail introduced context-sensitive ads and was unfairly pilloried for being anti-privacy or intrusive. And while there have been a few similar hand-slappings along the way, Google’s never faced a widespread backlash against their influence or dominance from average consumers yet. Today, protestations of “but it’s open source!” are being used to paper over real concerns about data ownership, and the truth is that open code doesn’t necessarily imply that average users are in control.

And ultimately, once a tech company becomes dominant in its space, it’s susceptible to a kind of reverse Hanlon’s razor: Anything caused by stupidity or carelessness will instead be attributed to malice. Similar to the Law of Fail (“Once a web community has decided to dislike an idea, the conversation will shift from criticizing the idea to become a competition about who can be most scathing in their condemnation.”), Google is entering the moment where it has to be over-careful not to offend, and extremely attentive to whether they are treading lightly.

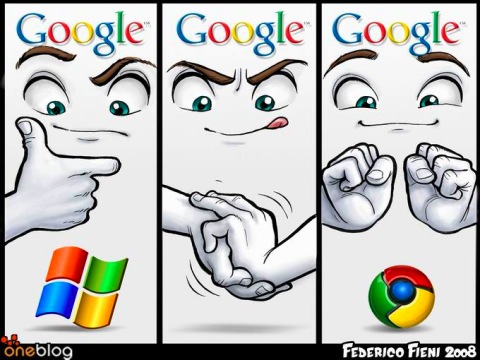

Is Google evil? It doesn’t matter. They’ve reached the point of corporate ambition and changing corporate culture that means they’re going to be perceived as if they are. Whether they’re able to truly internalize that lesson, accept it, and act accordingly will determine if they’re able to extend their dominance in the years to come. (Illustration courtesy of Federico Fieni.)

Related Reading:

- Google and Theory of Mind, from 2007.

- Google’s First Mistake, from 2003

- John Gruber this week, Putting What Little We Actually Know About Chrome OS Into Context

- A Pre-History of the Google Browser, from Chrome’s launch last year

- Google Web History : Good and Scary from 2007

Update: There’s been a phenomenal reaction to the ideas discussed here. I rounded up a lot of the responses in a follow-up post. But it’s also worth noting that a number of people from both within and without Google have pointed out that in many cases, the release of an Android application has preceded its counterpart iPhone equivalent due to delays in Apple’s opaque approval process for applications on that platform, or because the Android applications were only created as hobbyist projects by Googlers in their free time. Similarly, a number of people have pointed out significant differences between Chrome OS and Android, such as the primary development environments (HTML5 and Java, respectively), memory limitations for applications, and the distribution model.

While I’ve certainly not meant to gloss over any of these clarifications as insignificant, and appreciate the additional information, the key argument I’m advancing here is about the overall impact of changes in Google’s culture and perception. Many more examples can (and have) been identified to support that larger trend, and I’m pleased that the larger dialogue has focused on that bigger issue, inspiring some great conversation.