Why Tablet PCs Will Succeed

Microsoft’s been promoting its Tablet PCs for about a year now. Despite all the claims, they’re more evolutionary than revolutionary, of course. But that’s the not the surprising thing about them. The surprising thing about Tablet PCs is that they’re going to succeed.

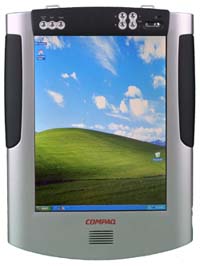

convertible tablet pc

convertible tablet pc

First, the basics: They’re laptop computers, most of them. Just like you’re already used to using. Due to a combination of cowardice and conservativism, every single design I’ve seen for a commercial Tablet PC is using the "convertible" design where the standard notebook design can be inverted (perverted?) by swiveling the screen 180 degrees and folding it back over the keyboard, covering it up and yielding a standalone screen that’s then viewed in portrait orientation instead of landscape. Ideally, they’d have super-light keyboardless versions of these, true digital slates to write on. But for now we’ll probably have to settle for transformable units in relatively standard configurations.

And they run pretty much standard desktop software. They use a version of Windows XP, with some bits and pieces tacked on to handle handwriting. The only distinct app that ships with them that you can’t get on an XP laptop right now is a program called Journal, which emulates a standard legal pad, complete with thin rules dividing up lines on the page.

What The Tablet Brings To The Table

Why, then, will these tablets succeed, despite commanding a several hundred dollar premium over standard laptops? Because they address the fundamental flaws in the user experience of current computers. Although it’s somewhat mitigated by the recent ubiquity of laptops, today’s computers reveal all too blatantly their history as personal computers. Desktop PCs require you to turn and face away from anyone you’re having a conversation with, and orient yourself to the screen you’re working on. Tangles of cables and cords wire your input devices to that screen which is monopolizing your eye contact. And while laptops at least let you nominally face a person you’re having a conversation with, they just won’t play nice in any work setting, where they just become smaller, less comfortable desktops.

The human factors are very telling. Think back to the highest-level meetings you’ve had in your career. Whatever major decision-maker or principal who was the Big Presence in the meeting almost certainly didn’t have a laptop with him in the conference room. If anything, he (yes, sadly, it was probably a he) had a standard legal pad and a big fat fancy pen. Maybe the legal pad was in a leather binder. The poor pasty lackey to his side, or maybe at the end of the table, had the laptop with the supporting data and relevant background information. The only, rare, exceptions to these arrangments are in extremely technical disciplines.

tablet pc prototype

tablet pc prototype

This dynamic has been established for a number of reasons. That the old suit probably didn’t know how to work a computer was undoubtedly high on the list. And he certainly wanted to impress upon those present that he was such an authority that he could command a tech lackey to handle "that computer stuff", of course. But the key thing was body language. A legal pad doesn’t interfere in a meeting. It doesn’t prevent a glower or glare or raised eyebrow the way that these human reactions are hidden when a person is turned to face a monitor or when shielded behind even the most svelte PowerBook screen.

Resting against the edge of a conference table, balanced on the knee of a crossed leg, tossed towards the middle of the table for emphasis, or slowly pushed across the table in a conciliatory gesture of resignation, that legal pad is a prop. It’s a symbol so powerful as to have become cliché.

And the Tablet PC is the first computer to recognize this essential bit of business playacting. Microsoft has for years been making hardware that recognizes human factors in a way that the Macintosh has, frustratingly, been amazingly unaware of. Mapping page navigation to a scroll wheel makes infinitely more sense than having a user target a tiny scroll button. Most bits of GUI widgetry probably ought to be represented in hardware, as well, if only to mitigate the Fitts of apoplexy induced by the high cost that current user interfaces exact for even the simplest of errors. Pressure-sensitive touch input is a pretty good step towards a more forgiving interaction between users and machines.

The rest is all fine, of course. It runs Office and Internet Explorer and all the crap you’re already doing. But Tablet PCs do a much more capable job of recognizing the Wi-Fi enabled, pervasively connected future. There’s an implicit assumption that these machines, or their descendents, will be used in social situations, in contexts where the only peers and networking that matter have to do with the humans that surround you.

Another liberation of pervasive computing is from the tyranny of the pen and pad. Jotting down notes is still the simplest, quickest method of shaping an idea in its crudest stages, or of documenting a conversation as it happens. And some people still tend to shape at least certain categories of thought on plain old pen and paper, even if they are otherwise extremely wired and technical users. Like, for example, me. Though these paper notes can’t be quickly searched, easily categorized and stored, or neatly edited, they succeed because they are not overburdened by interface and allow instantaneous sharing of the information they contain.

Apple’s made nods towards this reality, of course. The cheerful guy at the Apple Store who demoed the iMac for us made sure to pivot the screen (with the requisite extended fingertip) to show how you could "share your work with your friends". But I sit on the sofa next to my friends, or at a table with my co-workers. We face each other, not our common object of admiration. Granted, if I watched more TV, that might be a more frequent arrangement. But didn’t we go around shouting from the caboose of the ClueTrain that The Web Isn’t TV?

The Human Factor

In short, Tablet PCs, or their eventual heirs in the hardware realm, will succeed because they accommodate the human factors of collaboration better than any previous iteration of computer hardware. They won’t replace desktop PCs or laptops, of course, because sometimes people do need to work on their own, focused on the task at hand. But now we’ll also have the option of using a computer in social settings like a Starbucks or a conference room or during a lecture in a classroom without having to compromise our participation in the event.